Research Proposal Writing for Social Sciences: Understanding the Research Pyramid

How to write a proposal that integrates your literature review, research objective and questions, your methods and methodology?

Over the years I have been approached countless times by students and inexperienced researchers with questions about writing a research proposal for the social sciences. Often they have a draft, but the elements don’t hang together, the whole thing seems arbitrary, and they know it.

My advice has always been to take a step back from the research proposal text, and to take time to really understand what I call the ‘Research Hierarchy’, in order to think about how it applies to the project you are considering.

I’ve been asked this so many times that I thought it might be useful to put my answer in writing. I think this may be particularly helpful because the instructions on how to write research proposals are often pretty unclear. Understanding the fundamentals and the logic from first principles will help to produce an effective proposal, whether you’re applying for a masters or a PhD or for a grant.

Typical novice research proposals

Research proposals are often bad. In order to write a good one, it’s important to understand what problems commonly occur so that you can avoid them.

Novices often come with a lot of enthusiasm for a particular topic, some general knowledge about social theory, and research questions that come out of ‘applying’ the latter to the former. In other words, the ingredients of a novice research proposal are:

- Passion/insight

- Attractive/known methods and theories

- Research questions determined by (1) and (2)

For example:

- I will apply feminist theory to board game culture in order to understand gender relations among gamers.

- I will analyse Game of Thrones using semiotics in order to understand the use of symbols in modern television drama.

- I will use ethnographic methods to study clothing culture among London Underground commuters.

This approach often results in a research proposal that is paradoxically too humble and too ambitious.

By ‘too humble’, I mean that the writers of these kinds of proposals do not really imagined themselves taking part in a dialogue with academic research literature. They ‘apply’ theory, but they’re not in dialogue with it. This is probably OK, but not ideal at undergraduate level. Beyond that, a research project should realistically expect to contribute something to the conversation. Even a graduate student project? Yes absolutely. It’s not as difficult as it sounds, which brings me to the next point…

…By ‘too ambitious’, I mean that the researcher proposes a topic of research that is extremely broad. This is likely to result either in a very superficial treatment, or in an over complex method that may not be feasible in the time available. The way to avoid this problem is by narrowing the research objectives down to a manageable size. The best way to do that is to engage with existing literature and attempt a very precise, narrow way in which it can be improved.

The research pyramid

So now we know what to avoid. How do we improve on the novice research proposal?

The key thing is to understand that the elements of a research proposal—such as research objectives, methods, literature review and so on—are not there because they’re nice to have. They are related to each other in a logical and hierarchical manner.

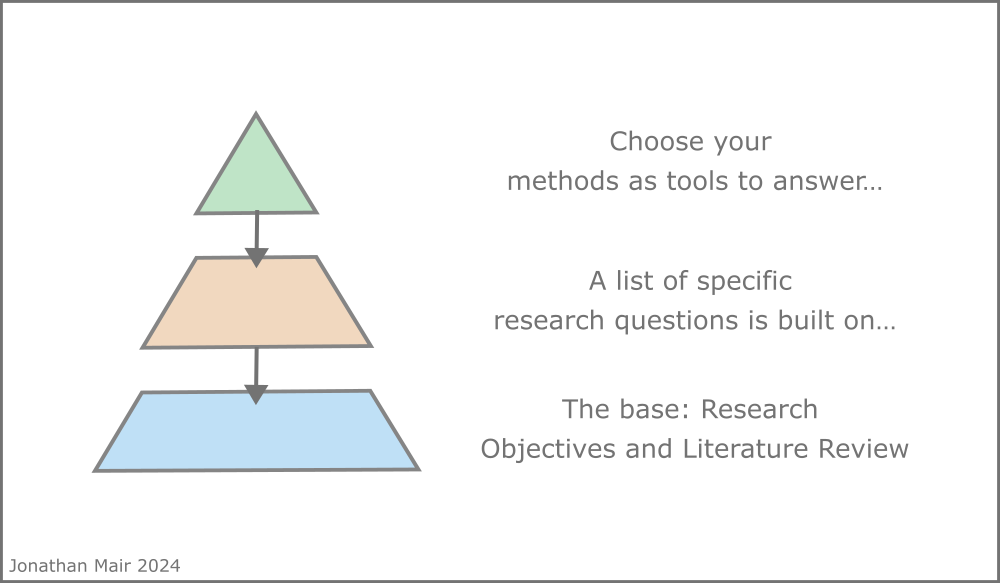

A research proposal is a pyramid with three layers. You don’t begin building a pyramid at the top, you build the base first, and the same is true of a research proposal.

Let me explain, layer by layer…

The base of the research pyramid: research objectives and literature review

The base layer of the research pyramid is made up of Research Objectives and Literature Review. These are on one level because they are in a reciprocal relationship. You need to work on them both at the same time.

You will probably begin with a general research objective. This will give you an initial orientation to begin your literature search. As you read, you will be able to think more clearly about your topic. You will make finer distinctions, and you will find out what people have already discovered about it.

For instance, say you want to research prizes and how they work as incentives. That orients you to the literature, and an initial search reveals that scholarly work on the topic divides prizes into two major kinds: ex post prizes, such as the Nobel Prizes, which award people for things they have already done, and ex ante prizes, which set a challenge beforehand, which people then respond to, in order to be judged.

Now you know that to make a contribution to the literature you will probably need to focus on one or the other, or perhaps interrogate that distinction itself. Otherwise your efforts will be begging the most basic question of prize studies!

So your research objectives will narrow and you will have a more focused orientation to the literature. You will learn more, and you will probably want to narrow your focus again.

This iterative process should continue until you’re happy that you have a focus that corresponds closely to the literature, but that is narrow enough that it will be easy for you to carry out.

The second layer of the research pyramid: research questions

Your research objective sets out the general issues you want to understand. How long will it take you to answer them? How long is a piece of string?

If you stay at the general level, it is impossible to guage whether a proposed research project is feasible in the time and with the resources available.

That is why you move from your general research objectives to specific research questions.

A research question should be specific enough to be able to say definitively whether you have answered it or not.

For example, a research objective might be to understand how intensely young people in Spain use social media apps. That’s a good research objective, but it will be hard to know whether we have definitively answered it or not.

A corresponding research question might be: In Spain’s biggest 4 cities, what proportion of people between 13 and 26 use social media apps for more than four hours a day. This is concrete question with a concrete answer. We will know when we have answered it and we can have a good guess about the resources needed to come to an answer. The same is no true of the research objective.

You are likely to have a range of specific research questions such as this. The number and variety will depend on the resources at your disposal.

The pinnacle: methods and methodology

You’ve identified the research questions that will help you to fulfil your research objectives and contribute to the debates you have identified in your literature review. Finally, it’s time to select your methods.

It’s right that you’re doing this last. Methods are a tool for answering questions. It doesn’t make sense to select your methods first and then find some questions to apply them to. That would be like selecting a tool and then deciding what home repairs to do, rather than deciding on a problem that needs fixing (objective), deciding how to fix it (research questions), and then looking for the right tool for the job.

(OK, there are important exceptions to this rule!)

Methods are the important bit here: what you will do, when and where. Methodology is the part that explains why these methods are suitable ways of going about answering your research questions.

To summarise

The research pyramid is a way to build a research proposal in three logically linked steps, building from foundation to pinnacle.

- Research objectives <–> Literature review: a reciprocal process in which you refine your thinking about a topic and identify a narrow aspect of the topic to which your research will contribute

- Research questions: specify the general research objectives in terms of answerable questions

- Methodology/Methods: appropriate for the specific research questions